When William Sealy Gosset joined the Guinness brewery in Dublin in 1899 as a chemist, he faced a practical problem: how could he ensure consistent quality in beer production when testing every hop flower and barley sample was economically impossible? Working with small batches meant small sample sizes, and the statistical methods of his era simply didn’t work well with limited data.

Gosset’s solution would transform not just brewing, but the entire scientific world. Through meticulous experimentation, including early Monte Carlo simulations using random numbers, he developed what became known as the t-test, a method for determining whether results from small samples represent genuine patterns or mere chance variation. The question “Is this batch of hops truly defective, or did we just get unlucky with our samples?” turned out to be fundamentally the same question researchers ask across medicine, psychology, agriculture, and countless other fields.

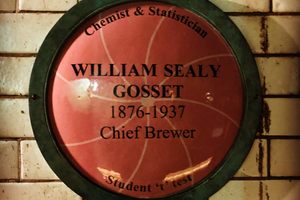

Here’s where the story gets delightfully peculiar: Guinness had prohibited employees from publishing research after a previous incident involving trade secrets. So Gosset published his groundbreaking 1908 paper under the pseudonym “Student” to avoid detection by his employer. This is why statistics textbooks still refer to “Student’s t-test” rather than the Gosset t-test, a quirk of corporate secrecy that accidentally erased his name from his own achievement.

The plaque, visible during Guinness Storehouse tours, recognizes this unlikely hero of modern science. Beneath his name and dates (1876–1937) appears his title “Chief Brewer” alongside “Student ‘t’ test” a perfect encapsulation of how the pursuit of the perfect pint accidentally gave the world one of its most essential analytical tools. Brewers demand consistency while vintners celebrate variation, and in this case, that obsession with uniformity inspired genuine innovation.

Gosset remained at Guinness throughout his career, eventually building a small statistics department and corresponding with luminaries like Ronald Fisher and Karl Pearson. He never sought fame for his discovery, content in the knowledge that he had solved real problems for his brewery while quietly revolutionizing how scientists everywhere interpret their data.